CHIP, Medicaid and the Federal Budget: Taking Stock of 2018

March 20, 2018 | Featured Articles

Although President Trump on Feb. 9 signed a two-year budget passed by Congress into law, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO)—even before passage of this budget—had calculated that the huge federal deficit would continue its upward trajectory. This budget raises the federal debt limit through September of 2019, and increases federal spending by trillions of dollars. Because of this the future economy of the country, though not yet visible, is skating around on ever-thinning ice.

The national debt will directly affect “safety net” funding.

An additional $2.4 trillion in national debt will accrue beyond the CBO’s reported dollar amount, according to findings from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Cutting “safety net” programs is a major goal of conservative Republican legislators as well as the Trump Administration. Therefore, limiting spending on health programs most beneficial to low-income, disabled, and elderly Americans—such as SNAP, CHIP and Medicaid—is now an even higher conservative congressional priority in order to decrease the future anticipated national debt.

Hospitals, health centers and medical providers serving disadvantaged communities consequently face uncertain futures in terms of financial reimbursement and long-term sustainability. And yet, these health programs in and of themselves produce significant savings to us as a comprehensive society.

CHIP decreases healthcare cost-burdens in the United States.

The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was created in 1997 to reduce the spread of contagious childhood diseases (thereby promoting public health). Families exceeding the Medicaid income eligibility threshold who are unable to afford health insurance are enabled by CHIP to obtain health coverage for their children. Coverage for pregnant women earning up to 185% of the federal poverty level is also offered through CHIP in 19 states (per a March of Dimes issue brief).

Besides reducing the likely high costs associated with treating adult health conditions linked to childhood illnesses (e.g., infections causing intestinal dysfunction), ensuring the capacity of kids to receive healthcare reduces the likelihood of their developing one of the following chronic conditions that can lead to dependency by age 50 on federal SSDI financial support:

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease;

- Type 2 Diabetes;

- Profound hearing loss/deafness;

- Blindness;

- Central nervous system deficits

Presented in the February 2017 issue of JAMA Pediatrics was that—in terms of total nationwide dollars spent— the top child healthcare category was well-newborn care (limited exclusively to babies delivered without complication). Not only does well-newborn care bolster infant normal growth and development, but it is also highly linked to cognitive and psychosocial development and functioning in adolescence and beyond.

Medicaid provided coverage for 50% of all US births in 2015, as well as half of all healthcare for children aged 0 to 3. Meanwhile, Title V-Maternal and Child Health Block Grant funding covered services for around 2.6 million pregnant women, 3.8 million infants, and 3.5 million toddlers aged 1-3. While Medicaid costs incurred for care of pregnant women and children aged 0 to 3 totaled $34 billion, CHIP costs totaled $2 billion. Yet Republicans in Congress nearly allowed CHIP funding to expire, leaving enrollees in several states without CHIP coverage from December 2017 until its inclusion in the budget in early 2018.

Of the nearly 81 million Medicaid recipients in 2014, only 27.4 million were adults. Eleven million those were permanently disabled individuals, and 7.3 million were elderly, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation report.

Even high-income seniors can quickly drain their financial resources in order to pay expenses related to catastrophic health events and/or assisted living or nursing home facilities. Since nursing homes require the loss of all financial resources before payment assistance is available, Medicaid was the primary payer of nursing home care in the United States as of 2017.

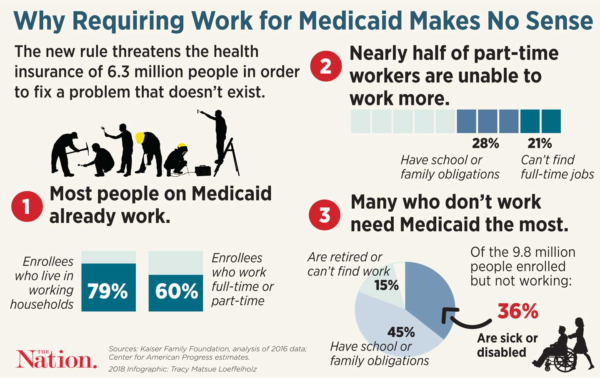

In a major federal policy shift, the Trump Administration enabled states to impose work requirements on non-disabled adult Medicaid recipients in January 2018. Seema Verma (nominated by President Trump to be Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) authorized this shift. Kentucky became the first state to acquire federal approval, but the following nine other states are seeking to enact Medicaid work requirements: Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Utah, and Wisconsin.

Case-in-point: Kentucky’s penalization of Medicaid recipients.

Twenty paid or volunteer work hours per week are now required to enroll in Medicaid in Kentucky. The state has enacted an additional requirement that Medicaid recipients pay monthly premiums, with a failure to pay by the due date resulting in loss of Medicaid coverage). The state of Kentucky anticipates that the new work requirement will result in 95,000 Medicaid beneficiaries dropped from enrollment over the next five years, according to findings by the American Association of Retired Persons.

Adding a work requirement for Medicaid eligibility may initially appear consistent with the work requirements under the federal SNAP or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program. However, there is a critical difference. Health directly affects the ability of an individual to hold a job. Chronically ill workers not only have higher absenteeism rates, but they also can negatively impact the functioning and productivity of a workplace.

The underlying shortsightedness of a Medicaid work requirement is the lack of recognition that many Medicaid recipients—while not considered permanently disabled—are coping with significant health conditions that preclude holding a job. For example, diabetic peripheral neuropathy can cause a burning sensation in the feet and hands, and back pain can make it difficult to sit for long time periods. Yet typical jobs available to adults with low educational and employment skill levels—the majority of Medicaid recipients—are either in the retail or service industries, both of which require either standing or sitting for long periods.

Self-employed individuals may experience a decrease in income due to a health (or other) catastrophe, and therefore qualify for Medicaid. Ironically, the Medicaid work requirement may eliminate the capacity for recipients to become self-sufficient through self-employment, or cause these self-employed individuals to simply forego renewing their Medicaid enrollment and develop disabling health disorders.

Medicaid work rules will negatively impact recovering substance abusers.

The Trump Administration declared the opioid epidemic a health emergency in November 2017, and the new budget allots $6 billion to fight the opioid epidemic (to be allocated by congressional members). For recovering alcohol and opioid abusers, attending substance-abuse treatment programs may be essential to preventing a relapse. Therefore, it is possible that losing Medicaid coverage due to an inability to work the required weekly hours may create an unintended vicious cycle of worsening the opioid abuse epidemic—instead of contributing to its resolution.

Funding for the Health Center and Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education Program programs has been drastically reduced.

Mandatory funding for these two programs expired in 2017, and the Republican-dominated Congress only voted to reauthorize—at reduced levels—their short-term funding through March 31, 2018, per the National Academy for State Health Policy.

The Health Resources and Services Administration website specifies that there are approximately 1,400 public health centers (operating more than 11,000 service delivery sites) across the US, and these serve nearly 26 million people. Notably, public health centers primarily serve Medicaid enrollees and other low-income patients. Meanwhile, the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education Program supports physician primary care residencies in low-income and medically underserved areas in 24 states; and primarily, in these health centers.

Public health center finances are well-recognized as typically strained, and $1.2 billion of the appropriated monies for public health centers in 2017 came from discretionary funding. There is consequently no guarantee that health center funding in 2018 will even remain at the same level as 2017. The Republican-promoted tax cut from December will likely reduce federal revenues, as well as spurring significant cuts to Medicaid and other programs aiding the poor.

Women’s access to contraception is being stymied.

Under President Trump, access to contraception is being thwarted on a myriad of fronts:

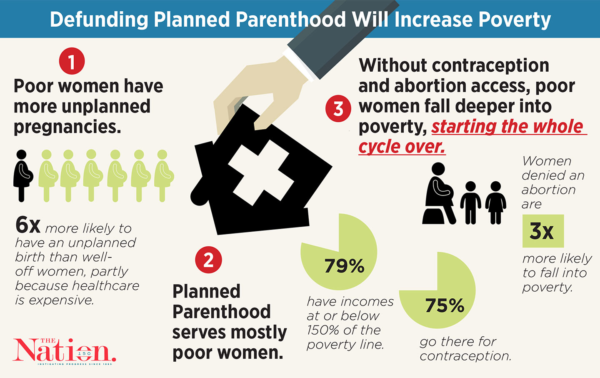

Front Number 1: Reversing state Medicaid guidance under President Obama, the Trump Administration issued guidance essentially enabling states to restrict Medicaid funding based on failure to meet state-determined provider qualifications—and specifically needed by states preferring to withhold reimbursement for services provided at Planned Parenthood clinics17, which in 2017 provided family planning services to 50% of Medicaid-enrolled women in most counties where the organization has clinics.

Front Number 2: The Title X family planning program enacted under President Nixon has enabled provision of free or low-cost contraceptives to low-income but Medicaid-ineligible women through federal funds administered to state health departments and family planning clinics. Title X currently funds family planning services at around 4,000 clinics that serve roughly 4 million women.

However, Title X federal funds for FY2018 remain unreleased while 60% of funded entities will have run out of Title X dollars by March 31.20 Meanwhile, the Title X application approval process in 2018 has been changed in accordance with Trump policy to emphasize funding of programs that include “abstinence only” and “natural” family planning methods.

Front Number 3: The Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated coverage for contraception by most private insurers, plus federally specific coverage requirements for family planning applicable to Medicaid (albeit with no existent federal definition of “family planning”). In contrast to the Obama Administration, expanding the range of employers that can exclude contraceptives from their employer-provided insurance is a Trump Administration goal.

The conclusion is a likely an unstable future.

The ACA mandated that states comply with a national baseline of health insurance coverage, rather than enact laws in opposition to that national standard. As states rights proponents, President Trump and congressional Republicans (along with Supreme Court Justice Gorsuch) prefer a limited federal oversight role, in tandem with greater state power over decision-making.

How does this bode for the country? The Wall Street Journal reports that Democratic- and Republican-controlled states are moving in opposite directions on health policy. One example of this is can be found in state requirements for short-term health plans, which most often do not cover preexisting conditions and maternity care. Given that Trump supports an increased availability of short-term health plans (with regulations left to states), some states are seeking to expand availability of these short-term plans. Others seek to restrict them.

The ripple effect is expected to promote increased instability for insurers and across the US healthcare system as roll-backs to ACA provisions continue under President Trump. It definitely does not take a crystal ball to know that we will most certainly be paying for this instability and lack of common sense for future decades to come.